Tissues on Demand Via Organ on a Chip: New Advance for Transplant Patients—and Drug Testing

A new technique for programming human stem cells to produce different types of tissue on demand has been developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), with support from the NSF-funded Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (Synberc), headquartered at the University of California (UC) Berkeley. The technique, which also has near-term implications for growing organ-like tissues on a chip, may ultimately allow personalized organs to be grown for transplant patients.

Growing organs on demand, using stem cells derived from patients themselves, could eliminate the lengthy wait that people in need of a transplant are often forced to endure before a donor organ becomes available. It could also reduce the risk of a patient’s immune system rejecting the transplant, since the tissue would be grown from the patient’s own cells, according to Ron Weiss, professor of biological engineering at MIT, who led the research. Using human stem cell-derived organ tissue to test new treatments could be far more reliable than testing on animals, since different species may react differently to a drug, he says. The technique could also allow clinicians to carry out patient-specific drug testing.

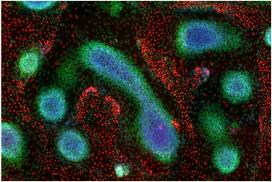

The researchers developed the new technique while investigating whether they could use stem cells to produce pancreatic beta cells for treating patients with diabetes. To do this, the researchers needed to devise a means to convert stem cells into pancreatic beta cells on demand. As a first step in this process, they took human stem cells generated from skin cells and converted them into “endoderm,” the innermost layer of cells or tissue of an embryo in early development, or parts thereof. Endoderm is one of the three primary cell types in a developing organism: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm make up the three germ layers (i.e., groups of cells in an embryo that interact with each other as the embryo develops) that contribute to nearly all the different cell types in the body. “They are the first real step of [cell] differentiation,” Weiss says.

The researchers developed a method to use a type of small molecule to induce the IPS cells to express a protein that can convert IPS cells into endoderm. After two weeks, the researchers found that the resulting endoderm had matured to form a liver “bud,” or small, rudimentary liver. Patrick Guye, a former postdoc in Weiss’ lab said, “This is especially exciting, as the process looks very similar if not identical to what is happening in the early liver bud in our own fetal development.”

Using human stem cell-derived organ tissue to test new treatments could be far more reliable than testing on animals, since different species may react differently to a drug. The technique could also allow clinicians to carry out patient-specific drug testing, including the interaction between different drugs they are taking, on their own liver-on-a-chip. The researchers now hope to investigate whether they can use the technique to grow other organs on demand, such as a pancreas.